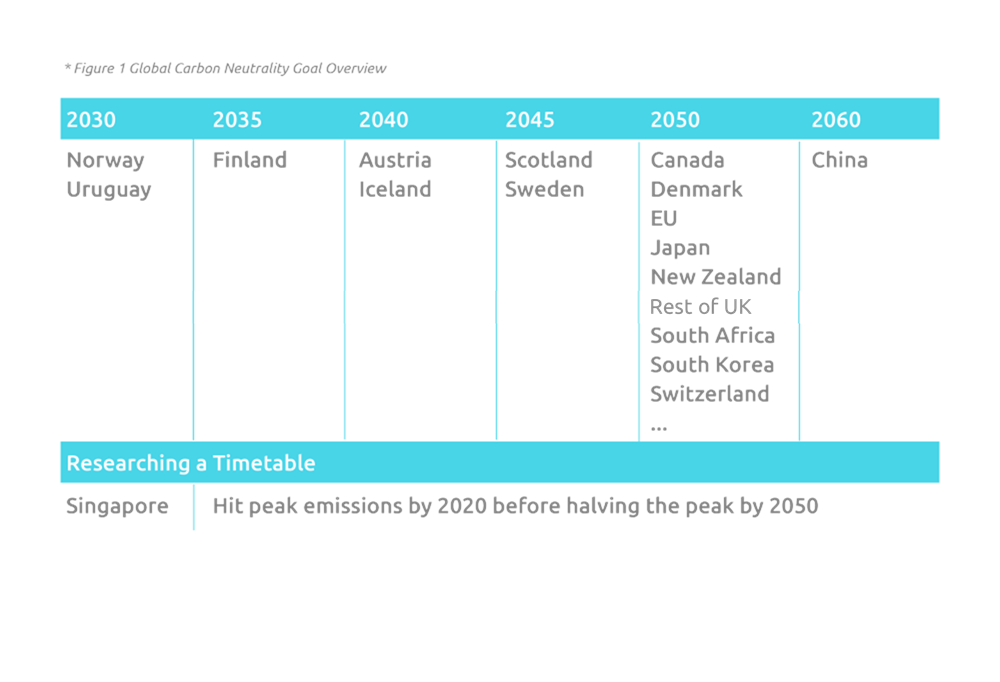

“Carbon neutrality” is achieved by balancing the emissions and absorption of carbon within a region, sector, or entity. Since the industrial revolution began in the mid-18th century, the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere has risen by 47%, causing the average temperature to increase by 1.2 degrees Celsius (36Kr, 2021). Climate change poses a threat to the environment and all living things, as well as society and economic stability. The landmark Paris Agreement signed by 191 states aims to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius, by the year 2100. However, the signatories’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are likely to enable a rise of 3.2 degrees Celsius, according to Wang (2021), which is why countries have announced separate emission goals from their NDCs. In November 2018, the European Commission declared a vision for a carbon-neutral Europe by 2050.

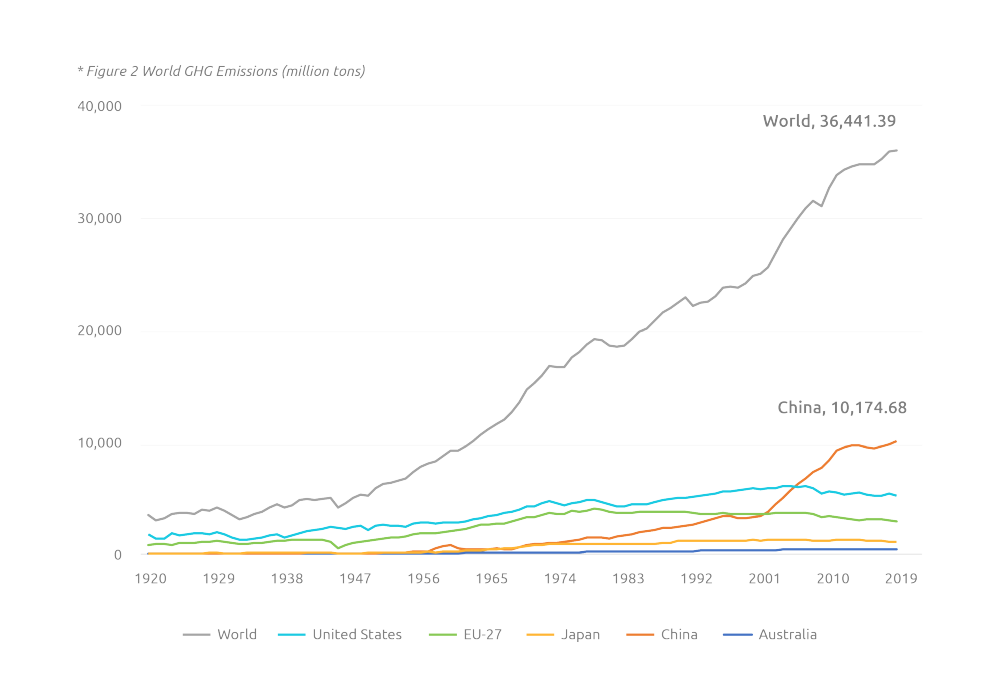

A groundbreaking moment for climate change mitigation came in September 2020 as China’s President Xi Jinping announced at the UN General Assembly that China would aim to hit peak emissions by 2030 before it becomes carbon neutral by 2060 (known as the 30-60 Goals). China’s pledge, followed by similar declarations by Japan and South Korea in October 2020, has put Asia in the spotlight. Although China has not joined the 2050 bandwagon, its 30-60 Goals will be a challenge given that they must be achieved amid relatively high economic growth, which contribute to high energy consumption and thus carbon emissions.

Following rapid economic development over the past few decades, China’s CO2 emissions in 2019 amounted to 10.175 billion tons (Ritchie & Roser, 2020) or 11.7 billion tons when other greenhouse gas emissions were included (Chen et al., 2020), which accounts for about 30% of global emissions. With various measures taken in energy production and use, the rise of emissions has been contained since 2011. Canada, the UK, France and Japan, which are among nations that strive to be carbon-neutral by 2050, are already past their peak emissions. Other countries such as Singapore hope to achieve carbon neutrality as soon as is viable in the second half of this century.

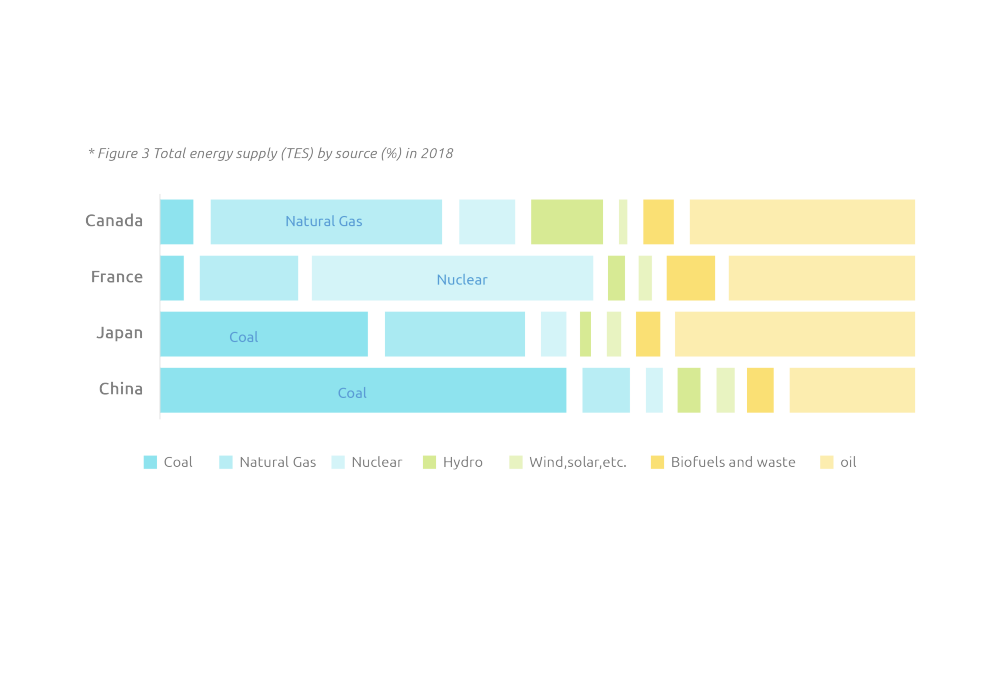

Asian countries, particularly China, Japan, and South Korea, do not share similar energy mixes with American or European countries. For countries like France where nuclear and other renewables dominate energy supply, the transition could be much easier through further electrification. China can only achieve its goals through increased adoption of renewables in electricity generation.

Since the announcement, policymakers have been working toward a low-carbon transition. It is generally perceived that increasing the share of electricity in final energy use, along with the share of renewables in power generation is the most promising road to carbon neutrality for China (Liu, 2020). Political support for decarbonization has also reached an all-time high this year, as underscored in the 14th Five-Year Plan. MioTech examines the policies and the changes they will make.

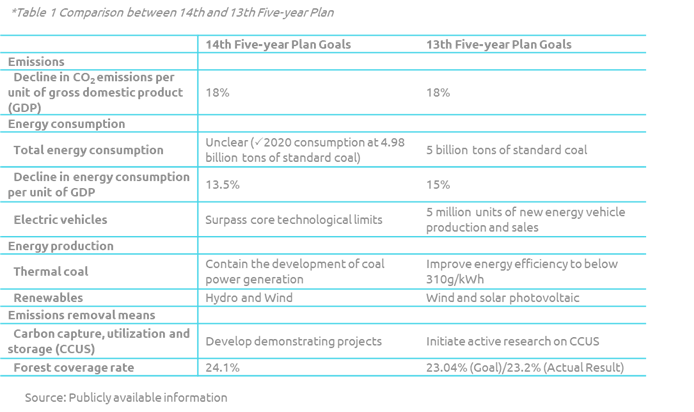

In the national 14th Five-year Plan, China has set a target for CO2 emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) to decline by 18% and energy consumption per unit of GDP by 13.5%. China has met its previous goal to limit total energy consumption below 5 billion tons of standard coal. China moves forward in phase out fossil fuel energy in the following five years by containing the development of coal power generation, restricting the construction of coal-fired power plants, and promote renewables like hydropower and wind. Relevant measures will also be adopted to increase the proportion of electricity as energy consumption and remove emissions.

Electrification to Optimize Final Energy Use Structure

Thus far 45% of energy output is used for electricity generation. This proportion is expected to rise to 85% by 2050 and by then electricity will account for 68% of final energy consumption, up from the current 25% (He, 2020). The adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is the most significant change toward higher electrification.

In the 13th Five-year Plan, an ambitious goal was set: 5 million units of either new energy vehicle (NEV) production or sales. During the 13th Five-year Plan, more than 5.04 million NEVs have been sold. Except for 2019 when annual NEV sales fell, a general trend of steady growth was maintained over this period. A recent news report also revealed that the current EV stock in China stands at 4.92 million and there are 1.68 million batteries at charging stations (Xu, 2021).

The 14th Five-year Plan have emphasized the importance of research and development into batteries and power systems to make advances. Like many other countries, China is convinced that the commercial vehicle sector has to be converted to electrification. The Plan notes that further actions must be taken to make city buses and delivery fleets electric-powered. Before the Plan, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) released an updated NEV subsidy policy, which includes a provision that a fuel cell industry chain should be established as soon as in four years.

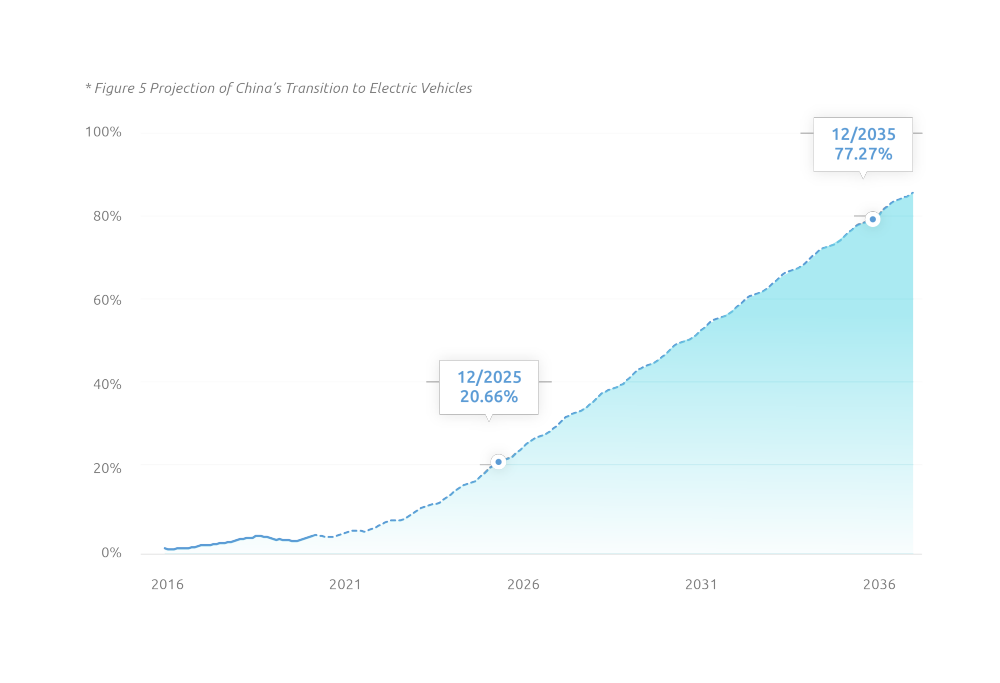

The long-term guidance to develop this industry can be found in the State Council’s Development Plan for the New Energy Vehicle Industry (2021-2035) published in November 2020. The plan sets out that 20% of the new vehicles sold in China by 2025 will be EVs, and BEV will be the mainstream energy source in the vehicle market. As of December 2020, BEVs accounted for 4.25% of new vehicles sold, according to CEIC Data, a figure that rose the following month to 4.61%. Expected annual growth is 1.2%, starting from 2022 and BEV market share in the entire vehicle market is forecast to exceed 20% by the end of 2025. By the end of 2035, more than 77% of new vehicles sold will be BEVs. The policy confirms the incremental withdrawal of subsidies with reductions of 20% and 30% in 2021 and 2022, before being removed by the end of 2022. MoF suggested replacing subsidies with incentives to encourage companies, while the industrial development plan stated that RMB4.5 billion had been allocated to reward the construction of vehicle-charging infrastructure.

Aside from transport electrification, the Five-Year Plan also addresses the issue of home heating, of which a substantial proportion is generated from coal in some areas. The government said it would work toward conversion to electric heat in these areas in the coming five years to reduce direct coal consumption. The Plan is also concerned about industrial decarbonization and encourages sectors and enterprises to reach peak emissions before the overall country does. More steel plants will be converted to low-emission production over the next five years. The steelmaking industry will reach peak emissions by 2025, while a detailed action plan to be issued, according to Li Xinchuang, chief engineer at the state-owned China Metallurgical Industry Planning and Research Institute (Z. Li, 2021). The metallurgical operations and the processing of ferrous metals accounted for nearly 18% of the carbon emissions nationwide in 2017, a proportion second only to power generation (Wu, 2021). Decarbonization will also extend to coking coal, clinker used in brickmaking and non-ferrous applications. The State Council also encouraged industries such as petrochemicals and construction to step up their transitions to low-carbon processes in a document released in February 2021.

Renewable Energy

The potentials of hydro and wind power generation have not yet been fully harnessed in China. The Five-Year Plan envisages a corridor of offshore power generation across five coastal provinces: Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Shandong,. The lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo (Brahmaputra) river will be a new base for hydro power generation. There is also a plan to develop nine areas of mass clean energy production encompassing hydro, onshore and offshore wind, and solar, as the figure shows.

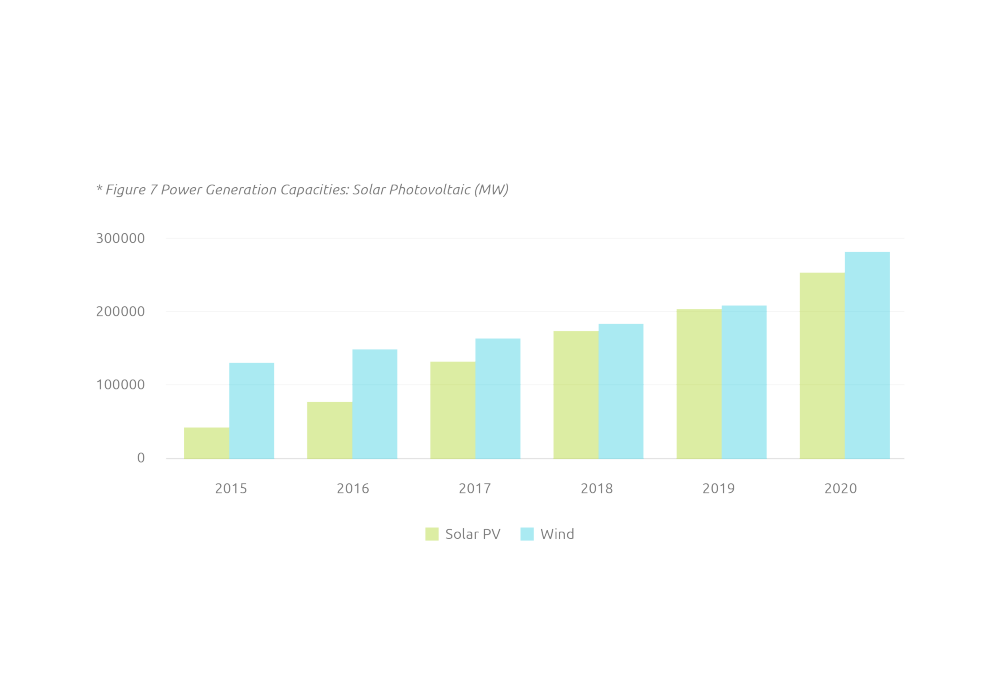

The 14th Five-Year Plan does not emphasize solar photovoltaic (PV) power as much as its predecessor, although newly installed solar PV capacities increased 24% to 253,430 MW in 2020. The total installed capacities of solar PV have been approaching those of wind in recent years. In November 2020, MoF published an announcement on renewable energy subsidies for 2021, detailing that there would be 3.38 billion yuan in the fiscal budget arranged to subsidize multiple types of solar PV projects in 10 provinces.

One key stakeholder, State Grid, has recently announced its decarbonization action plan, where it aims for distributed PV capabilities under its operation to reach 180 million kW by 2025, up from its 2019 level of 56.4 million (State Grid, 2020, 2021). By 2030, when the country is at peak emissions, State Grid will have 1 billion kW of wind and solar capabilities (compared with 450 million kW as of 2020). This is in addition to 280 million kW of hydro and 80 million kW of nuclear output (State Grid, 2021).

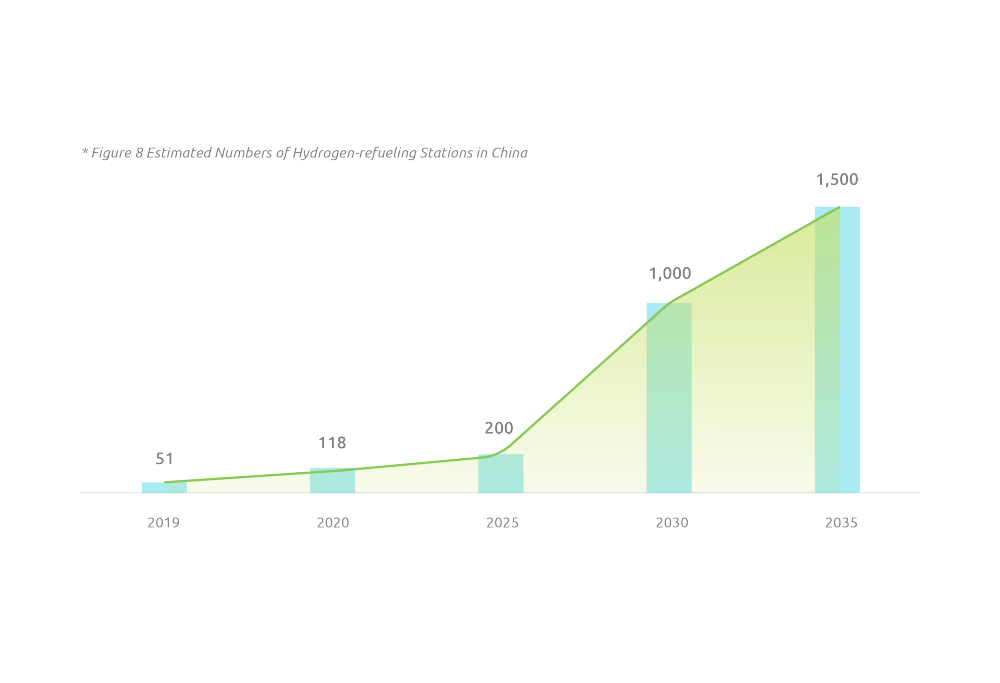

Though few details of development are given, the Five-Year Plan highlights hydrogen energy is regarded as a cutting-edge technology. Hydrogen energy made its first appearance in the Report on the Work of the Government in 2019, a year when 28 hydrogen-refueling stations were constructed, bringing the total to 51. By 2020, 118 were constructed with 101 in operation (Lin, 2021). China Hydrogen Alliance estimated that 200 hydrogen-refueling stations would be constructed by 2025 (China Hydrogen Alliance, 2019). A monograph on NEVs by MIIT noted that there would be 1,000 hydrogen-refueling stations in China by 2030. Some eight municipal governments have included the use of hydrogen energy in their own 14th five-year plans, especially Hebei, which wants to turn the city of Zhangjiakou into a hydrogen hub (Y. Li, 2021).

Offsetting Emissions

Policymakers have been paying more attention to the ecological environment since the “Beautiful China” strategy was unveiled at the National Conference on Environmental Protection in May 2018, which called for a cleanup of air, water and soil pollution by 2035. The creation of a carbon sink is one of the fundamental measures to neutralize carbon emissions. China’s forest coverage rose by 5.1 billion square kilometers (sq km) from 2015 to 2019, and stood at 23.2% of the total by 2019. The Plan expects that figure to rise to 24.1% by 2025. Additionally, based on China’s updated NDC to the Paris Agreement, forest coverage will increase by 6 billion sq km from 2005 to 2030, implying another 900 million sq km for the coming decade.

Municipal governments have set a target of a 1 % increase in forest coverage rate in the 14th five-year period as well. For example, Shanghai will raise the rate from 18.2% to 19.5 in part by creating 600 more parks in the city.

Following active research on carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) in the 13th five-year period, the current Plan has announced to develop demonstrating projects. Up to 21 large-scale CCUS facilities were in operation worldwide by 2020, including one in Jilin, that captures 600 kilotons of CO2 per year, according to IEA (2020).

Emission trading will also be more widely adopted, with the launch of a nationwide carbon trading market in Shanghai expected by June 2021. Based on a draft document released in November 2020, the trial rules for carbon emission trading are effective from 1 February 2021 after being approved by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) in December. Enterprises in specific industries and with total emissions of at least 26,000 tons per year will be subject to the new rules. The enterprises are allocated a certain emission allowance each year and they will be required to report their annual total emissions before the end of every next March for authorities to review. Currently, the rules only apply to the power generation sector and, according to the action plan on the determination and allocation of the allowances released on 30 December 2020, the list now includes 2,225 enterprises. On 29 September 2020, the MEE indicated in a news conference that in implementing the 14th Five-year Plan, sectors like steel and cement would be included in the emission trading as well. Involving more enterprises from different sectors will not only develop China’s emission trading market and assist the country’s transition to carbon neutrality, but also keep China in line with the global trend in climate change mitigation.

With eight pilot markets in operation at present, the new rules mark the beginning of a broad adoption of emission trading in China. According to the World Bank, the existing eight carbon markets in China cover 30% of the overall emissions (HUANG et al., 2020).

On 22 January 2021, the establishment of the Guangzhou Futures Exchange received regulatory approval, where carbon emissions futures might be traded -- carbon emissions futures and electricity futures would be the primary focus of their research. Reports on 18 March 2021 indicated that Shanghai would be the country’s emission trading hub, with Wuhan as the site of the national emission quota registration center (Zhou, 2021).

The Role of Finance

MEE, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and People’s Bank of China (PBoC), among other authorities, are coordinating to enhance the environment for financial investments to tackle climate change, according to their joint document released on 20 October 2020. A preferential system for climate-related investments would be launched by 2022, and policies and standards would be finalized by 2025, the agencies indicated. Notably, one of the agencies involved is the China Securities Regulatory Commission, implying that the securities markets will also be involved.

Banking regulators plan to assess financial institutions on the quantitative and qualitative performance for green finance, according to the “Evaluation scheme of bank's performance in green finance” released by PBoC in July 2020. The central bank will evaluate 80% of the total result by quantitative evaluation, such as the amounts of financing allocated for green loans and bonds, and how are they compared year-on-year, the remaining 20% being qualitative. Performance in green banking will be taken into consideration by PBoC when it rates a bank according to its macro prudential assessment guidelines.

Early Moves

Despite the national goal of hitting peak emissions by 2030, a variety of municipal governments are preparing for a quicker path . Specifically, Shanghai, in its own 14th Five-year Plan, indicates that the city should hit peak emissions by 2025, five years ahead of the whole country. Peak emissions and carbon neutrality are frequent terms seen in provincial 14th five-year plans, including that of Jiangsu, Guangdong, and Hainan, all with a purpose to move the peak-emission deadline forward. Fujian confirmed that a detailed plan would be made in 2021 and the provincial government will support two of its cities – Xiamen and Nanping – to map out a more efficient timetable. Hong Kong, the economy of which is dominated by the service sector instead of industry, is on track for carbon neutrality as soon as before 2050, according to Chief Executive Carrie Lam in her 2020 Policy Address. The city has reached peak emissions in 2014. Hong Kong will update its climate action plan in mid-2021 to detail the measures taken to reduce emissions.

Also, companies that do not derive most of their revenue from manufacturing have joined the bandwagon. Internet giant Tencent, being one of the first, announced in January 2021 that it had started making a plan to achieve carbon neutrality. Measures include integrating artificial intelligence and cloud computing in its data centers and headquarters, as well as improving its lighting system to reduce energy use. Ant Group announced in March 2021 that the company would achieve carbon neutrality in its supply chain and business travel and among the group’s subsidiaries by 2030. Ant Group is also going to start decarbonization of its office operations by reducing energy.

References:

36Kr. (2021). 光伏,碳中和“中军”:休息是为了更好的出发. Retrieved from https://www.36kr.com/p/1149949796320644

Chen, B., Fæste, L., Jacobsen, R., Kong, M. T., Lu, D., & Palme, T. (2020). A Climate Change Action Plan for China. Retrieved from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/how-china-can-achieve-carbon-neutrality-by-2060

China Hydrogen Alliance. (2019). 中国氢能源及燃料电池产业白皮书. Retrieved from 北京:

He, J. (2020). PPT分享|中国低碳发展与转型路径研究成果介绍. In. Beijing: ICCSD, Tsinghua University.

HUANG, D., SANTIKARN, M., MOK, R., CUI, Y., WANG, Y., & LIU, H. (2020). 全国碳排放权交易市场如何支持中国向碳中和过渡. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/zh-hans/voices/how-chinas-national-carbon-market-can-support-its-transition-carbon-neutrality

IEA. (2020). CCUS in clean energy transitions. Retrieved from France:

Li, Y. (2021). 多省将氢能纳入十四五规划,产业迎黄金发展期(附股)丨行业风口. Retrieved from https://www.yicai.com/news/100915861.html

Li, Z. (2021). 钢铁行业规划2025年碳达峰:相关行动方案正在编制.

Lin, C. (2021). 加氢站布局哪省强:广东第一,山东上海紧随其后. Retrieved from https://www.yicai.com/news/100906529.html

Liu, Z. (2020). 实现碳达峰碳中和的根本途径. 学习时报, 2021-03-15, 008.

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2020). CO2 emissions. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions#

State Grid. (2020). 2019 Corporate Social Responsibility Report. Retrieved from

State Grid. (2021). “碳达峰、碳中和”行动方案 [Press release]

Wang, S. (2021). 面向“碳中和”:“十四五”需要怎样的新增长路径?. 中国改革, 2021年第1期.

Wu, J. (2021). 低碳经济:选择题还是填空题 Retrieved from https://opinion.caixin.com/2021-03-26/101680711.html

Xu, N. (2021). 政协委员苗圩:加快充换电设施建设,减少里程焦虑,促进节能减排. 新京报.

Zhou, J. (2021). 全国碳交易市场如何聚“碳”成“财”?. Shanghai Securities News.